Tips to naturally lower cholesterol

Over one billion pounds a year is spent on statins in the UK. For some people, particularly those with heart problems, diabetes or high blood pressure, these drugs are essential in order to reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke and peripheral vascular disease. For many others, however, statin use, and the various side effects these drugs cause, could be avoided by adopting evidence-based lifestyle strategies.

This page provides information on what prompts our body to make more cholesterol than we need, while also outlining how to naturally lower cholesterol with diet, exercise and anti-inflammatory strategies.

What is cholesterol?

Cholesterol is a sterol (modified steroid) that is an essential structural component of animal cell membranes and a building block for the biosynthesis of steroid hormones such as testosterone, bile acids and vitamin D. Although it has many important functions, epidemiological studies strongly link high levels of cholesterol in the bloodstream with an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, dementia and other neurodegenerative disorders, as well as cancer development and its progression after diagnosis.

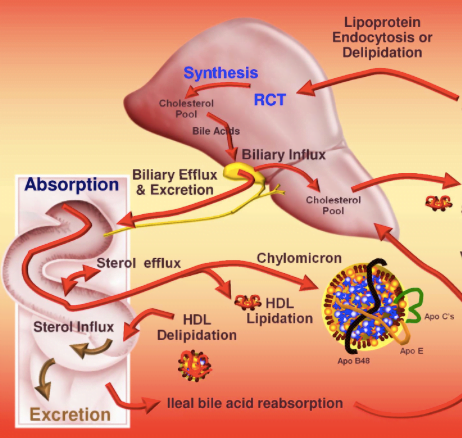

How cholesterol is absorbed and secreted

How is cholesterol transported around the body

Cholesterol is transported around the body by lipoproteins. The total level of lipoproteins measured in the bloodstream should ideally be less than 5mmol/L or less for healthy adults, and less than 4mmol/L for people with a high cardiac risk. A lipoprotein with a low protein: cholesterol ratio is called a low-density lipoprotein (LDL), while one with a high protein: cholesterol ratio is a high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

- High-density lipoprotein (HDL) – carries cholesterol away from the cells and back to the liver, where it’s either broken down or passed out of the body as bile. For this reason, HDL is referred to as “good cholesterol”, and higher levels are better (1mmol/L or more).

- Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) – carries cholesterol to the cells that need it, but if there’s too much cholesterol for the cells to use, it can build up in the artery walls, leading to disease of the arteries. For this reason, LDL is known as “bad cholesterol”, and it is better to have lower levels (3mmol/L or less).

.

What influences cholesterol levels

The absorption/excretion circulation pathways, illustrated above, highlight how raised serum levels are complex and influenced by a host of genetic, environmental, dietary and biological factors. Here are some “controllable” lifestyle factors which could help lower cholesterol to acceptable levels:

Lack of physical activity

Excess dietary cholesterol and saturated fat intake

- Butter, lard

- Pies, cakes and biscuits

- Fatty cuts of meat, sausages, bacon

- Cheese, cream and products made with them

- Shrimp and lobster

Higher intake of transfats

These are man-made in a process in which unsaturated vegetable oils are partially hydrogenated to produce saturated fats. This alters the melting point and freezing points, making them useful for margarine, snack foods, packaged baked goods and frying fast food. Apart from energy, trans-fats have little nutritional value and, by raising levels of LDL and lowering HDL, have been consistently shown to be associated with an increased risk of heart disease. Fortunately, awareness of their health risks and pressure on the food industry is reducing their use.

Low intake of polyunsaturated (healthy) fats

Short-chain omega 3, consisting of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) and eicosatetraenoic acid (ETA), is found in walnuts, edible seeds, clary sage, algal oil, flaxseeds and flaxseed oils, sacha inchi, echium and hemp oils. Long-chain omega 3, consisting of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are found in algae, edible seaweed, phytoplankton, oily fish such as herring, mackerel, salmon, menhaden and sardine, as well as cod liver, squid, krill oils and other marine foods. DHA is the primary structural component of the human brain, skin and retina.

Most omega-6 fatty acids originate from vegetable oils, nuts, grape seed oil, soya, flaxseed and oily vegetables such as avocado. Linoleic acid, the shortest-chained omega-6 fatty acid, is essential because the human body cannot synthesise it. The other omega 6’s can occur in smaller amounts in various and include gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), Di Homo gamma linoleic acid (DGLA) and Arachidonic acid (AA). These omega 6’s are generally synthesised by the body.

The trouble with a typical western diet is that is becoming increasingly low in omega 3, in part because the animals we eat are rarely able to roam free and eat a varied diet. As a consequence, the ratio of omega 3 to 6 consumption is changing to 10-20:1, when ideally it should be 3-4:1. The best way to improve this ratio is to eat oily fish 2-3 times a week as part of a regular balanced diet.

Sources of polyunsaturated fatty acids include:

Fish: The most widely available source of unsaturated fats and essential long-chain n-3 fatty acids EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) is cold-water, oily fish. Interestingly, fish do not synthesize them; they obtain them from the algae and plankton they eat. Fish with the highest levels include mackerel, salmon, herring, anchovies, pollock, shark, swordfish, sardines and, to a lesser extent, tuna. These fish have around seven times as much n−3 as n−6. Consumers of oily fish should be aware of the potential presence of heavy metals such as mercury and cadmium (from discarded batteries), as well as chemicals such as dioxin. As these accumulate in the food chain, larger fish such as shark and swordfish have the highest levels. It is suggested that their intake should be limited to twice a week (which is still more than the majority of people currently consume in a western diet). However, after an extensive review of the evidence, Harvard’s School of Public Health reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that the benefits of fish intake generally far outweigh the potential risks. Contamination is even lower in white, sea fish such as bass and bream, and no limits have been set on their consumption, although these have lower omega 3 levels. Freshwater fish such as trout and lake varieties are almost completely free of potential heavy metal contamination and have good levels of omega 3. Some protection from mercury contamination can be gained from eating foods rich in selenium (brazil nuts, crab meat), as this metal can bind to the mercury and stop it being absorbed into the body.

Linseeds (flax seeds) and the healthy oil it produces have a very high percentage of unsaturated to saturated fats. It also contains a high percentage of omega-3 content, six-times richer than most fish oils, albeit in the short-chain form (alpha-linoleic acid).

Avocado has the highest oil content of all fruits, and most of its fats are unsaturated, monounsaturated and omega-9. Other natural sources of healthy fats include rapeseed oil, which is particularly cheap as it can be grown in northern European countries.

Nuts almost all contain a good percentage of unsaturated fats. Walnuts are one of few nuts that contain appreciable omega-3, with the ratio between omega 3 and 6 being approximately 1:4.

Kiwi fruit has an even better ratio of omega 3-6, but there are only small quantities of oil in kiwi’s as opposed to linseeds.

Microalgae are rich sources of the longer-chain omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) and can be produced commercially in bioreactors. This is the only source of DHA acceptable to vegans. Brown algae (kelp) is also an excellent source of EPA.

Other plant-based foods with a good ratio of omega 3-6 include acai, seaweed, butternuts, chai sage, shiso and lingonberry. The leafy green vegetable Portulaca oleracea (Purslane) has the highest omega 3 levels of green vegetables but is very rarely used in western cooking. Some vegetables contain a small amount of omega 3, notably strawberries and broccoli.

Extracted plant oils used for cooking or salads contain a mixture of saturated and unsaturated fats. Linseed (flax seeds), olive and rapeseed (canola) oils have a particularly good percentage of unsaturated fats. Sunflower, soya bean and corn oil all contain mostly polyunsaturated fats, but tend to be heavily processed during manufacturing. Palm and coconuts have the highest percentage of saturated fats, making them energy-rich and potentially unhealthy, although cold-pressed varieties can still be healthy. In terms of the omega 3-6 ratio, the best oils are linseed, rapeseed, soybean and olive (which also has omega-9). Oils from microalgae and kelp contain the highest DHA and EPA levels and are usually taken as a supplement rather than used for cooking. Sunflower, palm kernel, cottonseed, grapeseed and corn oil contain virtually no omega-3.

In regard to meat, if you have high cholesterol, lower your intake and buy grass-fed animals, particularly game. Chickens which roam around eating grass, worms and insects, as well as grain, generally have much higher omega-3.

Eggs can be a good source of omega 3 (mostly ALA) and protein, but only if produced by chickens fed a diet of greens and insects rather than corn or soybeans. In addition to feeding chickens insects and greens, fish oils may be added to their diet in order to increase fatty acid concentrations in eggs. The addition of flax, chia and canola seeds to the diet of chickens, both good sources of alpha-linolenic acid, increases the omega-3 content of eggs, yet is very rarely done for mass-produced chicken eggs.

Milk and cheese from grass-fed cows may also be good sources of omega-3. One UK study showed that half a pint of milk from grass feed cows provides 10% of the recommended daily intake (RDI) of ALA, while a piece of organic cheese may provide up to 88%.

Higher processed sugar intake

Gut health and probiotics

Gut health and probiotics

Research presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions reported that a formulation of Lactobacillus may be able to reduce blood levels of LDL (bad cholesterol). A total of 60 people between the ages of 18-65 took part in the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The group taking the probiotic strains experienced, on average, reductions in total cholesterol levels of 13.6%. Probiotic bacteria reduce cholesterol by producing significant levels of bile salt hydrolase, which is effective at metabolising bile salts that contain cholesterol. These healthy strains are also able to incorporate dietary fat into their bacterial cellular surface, reducing the absorption of saturated fat. When considering a probiotic choice one which has been used in clinical studies (so has high quality assurance) contains mainly lactobacillus and combines inulin (prebiotic) and vitamin D…Read more.

Apart from a good probiotic supplement, there is a lot we can do to improve our gut health including eating probiotic rich foods such as fermented kimchi and kefir as well as prebiotic rich foods such as beans artichokes and mushrooms …. read more

Dietary phytochemicals and polyphenols

The are several categories of phytochemicals, including the largest group of polyphenols. For more information on how these have been categorised together with the foods they originate from click here. Foods with higher phytochemical content include:

- Pomegranate and other fruits

- Ginger and cranberries

- Leafy green vegetables

- Broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables

- Onions

- Chocolate (unsweetened of course)

- Turmeric and other herbs and spices

- Teas

Dietary phytosterols

- Avocados

- Flaxseed, Peanuts,

- Soy beans and Chickpeas

- Pumpkin seeds,

- Beans, Buckwheat

- Grains, vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds

Regular intake of these foods is linked to lower serum cholesterol levels, as highlighted in a recent meta-analysis of 41 trials which highlighted how 2-3 g of phytosterols per day reduced low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by about 10%. The beneficial effects were also found to be additive when combined with other lifestyle interventions. For example, eating foods low in saturated fat and cholesterol and high in phytosterols reduced LDL by up to 20%, while eating them with statin medication almost doubled their cholesterol-lowering capacity.

Plant sterol and stanol supplements: A dietary supplement is regarded by many as a convenient way to boost daily plant sterol intake. Studies have suggested that these can lower cholesterol by 20%, especially if combined with other lifestyle measures, reducing future cardiovascular risk and mitigating the need for statins. Sterol supplements would also be very useful for individuals who are already taking statins but are suffering side-effects, as studies show they enhance the LDL-lowering effects of the drugs. Instead of stopping statins altogether, people with side effects may be better off lowering their dosage and taking a concomitant plant sterol supplement at the same time. There are some safety issues related to a very high intake of plant esters sterols (>3g / day), with an increase of serum plant sterol levels linked to an increased risk of atherosclerosis. This risk is largely hypothetical, and the reality is that, in a western diet, consumption of plant sterols is usually much less than 0.5g / day, meaning individuals can safely be advised to eat considerably more of these foods and even take a sterol supplement. Another potential concern with very high doses is that they could potentially affect the absorption of carotenoids and fat-soluble vitamins. This, in theory, constitutes a hazard to children, as well as pregnant and breastfeeding women. Because of this, labelling advises these individuals against consuming these products, despite meta-analyses not demonstrating lower vitamin A, D, E and K levels after plant sterol intake. Nevertheless, general advice when taking a sterol or stanol supplement is to ensure adequate intake of carotene-rich foods such as carrots, pumpkins, squash, broccoli, apricot and mango. It should also be noted that nutritional supplements and functional foods can be enriched with saturated, less absorbable plant stanol esters which not only reduce serum cholesterol on their own but also reduce plant sterol levels in the bloodstream. The safety and efficacy of plant stanol esters have been confirmed in more than 70 published clinical studies, which show that daily intake of 2g lowers LDL-cholesterol by 10%, on average.

Summary

- Exercise most days and avoid periods of inactivity

- Reduce overall energy intake and aim for overnight fasting (no food for 13 hours)

- Reduce intake of cholesterol and saturated fat-rich foods

- Eat less meat and more plants

- Increase polyunsaturated fatty acid intake

- Stop eating processed sugar

- Increase intake of polyphenol-rich foods

- Increase intake of plant sterols (esters and stanols)

- Increase probiotic bacteria intake to help maintain gut health

In conclusion,

foods which contain lower levels of saturated fats and higher levels of unsaturated fats reduce the risk of cancer, decrease cholesterol and low-density lipoproteins (LDL-bad fats), reduce blood pressure and lower the risk of cardiovascular disease including strokes and heart attacks. Foods which contain higher levels of omega 3 (particularly the longer chain varieties EPA and DHA) are thought to also protect individuals from degenerative disorders such as dementia, poor eyesight and Parkinson’s disease. It would be very wise to ask your doctor to measure your lipid profile with a fasting blood test. If your cholesterol or LDL is high, it’s time to change the type of fat you eat.

If these dietary measures don’t reduce your total cholesterol or improve the ratio of LDL (Bad) to HLDL (good) cholesterol, then it may be wise to consider supplementation with polyphenols, plant sterols and stanols, and a good quality probiotic.

References

Rosin S et al. Optimal Use of Plant Stanol Ester in the Management of Hypercholesterolemia. Cholesterol 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/706970

Hallikainen MA, et al Comparison of the effects of plant sterol ester and plant stanol ester-enriched margarines in lowering serum cholesterol concentrations in hypercholesterolaemic subjects on a low-fat diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000 54(9):715-25.

Katan MB, Grundy SM, Jones P, Law M, Miettinen T, Paoletti R. Efficacy and safety of plant stanols and sterols in the management of blood cholesterol levels. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:965–978. [PubMed]

Welsh J, Sharma A, Abramson J et al Caloric sweetener consumption and dyslipidemia among US adults.2010 JAMA 21; 303(15),1490-7.

Kitahara C, de González B, Jee S et al Total Cholesterol and Cancer Risk in a Large Prospective Study. 2011 J Clin Oncol 29:1592-98.

Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Jim Mann J et al Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies BMJ 2013;346:e7492

Kitahara C, de González B, Jee S et al Total Cholesterol and Cancer Risk in a Large Prospective Study. 2011 J Clin Oncol 29:1592-98.

Yang J Chan D, Felix E et al A Sucrose-Enriched Diet Promotes Tumorigenesis in Mammary Gland in Part through the 12-Lipoxygenase (inflammatory) pathway. 2015 Cancer Res; 76(1); 24–29.

Platz EA, Clinton SK and Giovannucci E. Association between plasma cholesterol and prostate cancer in the PSA era. Int J Cancer 2008;123(7):1693-1698.

Chomistek AK, et al. Vigorous Physical Activity, Mediating Biomarkers, and Risk of Myocardial Infarction. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43(10):1884-1890.

Rock CL, et al. Results of the Exercise and Nutrition to Enhance Recovery and Good Health for You (ENERGY) Trial: A Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention in Overweight or Obese Breast Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(28):3169-3176.

Friedenreich CM, et al. Alberta physical activity and postmenopausal breast cancer prevention trial: sex hormone changes. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(9):1458-1466.

Foster-Schubert K, et al. Effect of diet and exercise, alone or combined, on weight and body composition in overweight-to-obese post-menopausal women. Obesity 2012;20(8):1628–1638.

Fuentes M, et al 2013. Cholesterol-lowering efficacy of Lactobacillus plantarum CECT 7257, 7528 and 7529 in hypercholesterolaemic adults. British Journal of Nutrition, Volume 109, Issue 10, May 2013 pp 1866-1872.

Bosch M, et al 2013. Lactobacillus plantarum CECT 7527, 7528 and 7529: probiotic candidates to reduce cholesterol levels. Journal of the science of food and agriculture: 2013, Nov pg.

Leave A Comment