An increasing body of evidence shows that poor gut health leads to premature ageing and is the cornerstone to many symptoms and diseases not only in the gut but elsewhere in the body. Radiotherapy, chemotherapy and ingested chemicals can damage the gut directly but dietary and lifestyle factors which affect the profile and diversity of the bacteria is most relevant for the majority of us (The gut microbiome).

There are trillions of these bacteria in our gut as well as lungs, skin, genital tracks. In fact, it has been estimated that there is more genetic material from these foreign organism that than in our own cells. We are not talking about bacteria which cause food poisoning (pathogenic bacteria) which causes acute illness but bacteria which colonise the gut for years. Put simply, some of these are classed as “bad” as they can promote chronic inflammation and others are classed as healthy or “good” gut bacteria, because they reduce inflammation and work with the body to strength gut integrity (prevent leaky gut) improve gut and general immunity.

The consequences of poor gut health

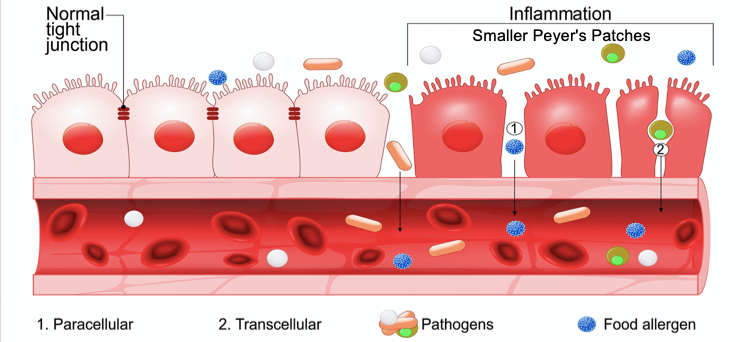

Excess chronic inflammation of the gut wall caused by too many pro-inflammatory (bad ) bacteria over time will thin and damage the integrity of the gut wall. The same problem occurs in people intolerant to foods such as gluten, lactose and lectin, because they have increased concentration of a gut protein called zonulin, which also signals the junctions to open up.

Excess chronic inflammation of the gut wall caused by too many pro-inflammatory (bad ) bacteria over time will thin and damage the integrity of the gut wall. The same problem occurs in people intolerant to foods such as gluten, lactose and lectin, because they have increased concentration of a gut protein called zonulin, which also signals the junctions to open up.

Poor microbiota reduces butyrate levels, which means less fuel for new cell growth. Consequently, the dead cells that are being naturally sloughed off cannot be replaced quickly enough, leading to a thinning of the gut wall.

The adjacent picture shows that, in this situation, the increased, poorly functioning gaps between cells allows partially digested food and other harmful organisms to penetrate the tissue beneath it. This reduced integrity has been nick named leaky gut syndrome which allows toxins, including carcinogens, into the bloodstream it causes vitamins, minerals, polyphenols and proteins to leak into the gut depriving the body of the these essential nutrients, reducing antioxidant and immune efficiency.

Poor Gut Health – symptoms and diseases:

Poor Gut Health – symptoms and diseases:

Some people live with poor gut health for years without noticing although may have to take more medication such as antacids, anti-spasmodics and laxatives.

Indigestion and ulcers: Most people with poor gut health suffer from bloating, unsatisfactory bowel movements, excess offensive wind, pain, constipation and diarrhoea and indigestion. In severe cases, this can lead to stomach ulcers, and if an ulcer is further irritated by acid in the stomach and duodenum, it can erode an artery, causing fatal bleeding.

Cancer: Scientific evidence strongly suggests that a diverse bacterial microbiome can protect us from cancer by outcompeting (displacing) cancer-causing pathogens and reducing inflammation. The immune responses to gut bacteria can also help stimulate immune responses against cancer cells. Studies have recently discovered that particular species of gut bacteria (particularly lactobacillus) increase the therapeutic benefit of chemotherapy and targeted biological therapies for melanoma and other cancers. These findings suggest that individual differences in microbiome composition is one of the reasons these immunotherapies work better for some people than others.

Digestive issues: Poor gut health, has been linked to an increased risk of food poisoning including Helicobacteria, food intolerance, food allergies and Inflammatory bowel disease.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) – With methane producing “Bad” bacteria causing nausea, bloating, fatigue, weight loss. (The main drive of treatment would be to increase gut motility with daily exercises such as running, increasing anti-inflammatory phytochemical rich foods and prebiotics and increasing fermented lactobacillus rich foods which displace the bad bacteria with good bacteria)

Symptoms and diseases outside the gut:

A leaky poorly functioning gut, as well as cancer cause general distressing symptoms which have a significant impact on quality of life. The most well known systemic links to poor gut health include:

- Fatigue and low mood

- Reduced sports performance

- More colds and flu

- Arthritis

- Osteoporosis

- Eczema and atopic skin conditions

- Diabetes

- Cholesterol

- Heart disease

- Dementia and Parkinson’s disease

- Premature ageing

Lifestyle measures which influence our gut microbiome

There is still a lot we do not know about our microbiome – Unhealthy bacteria tend to dominate more as people get older. Here are the lifestyle and dietary factors which affect gut health:

Non-nutritional factors:

- Obesity

- Smoking

- Regular exercise can improve gut health, while extreme exhaustive exercise ca cause it to deteriorate

- Depression and stress

- Taking antibiotics

- Following chemotherapy and radiotherapy

- During and after a viral infection (especially covid)

- Taking antacids

Dietary factors

Foods are linked to poor gut health include:

- High fatty meat intake

- Excess alcohol – especially beer and spirits

- Processed sugar

- Artificial sweeteners

Healthy bacteria rich foods which promote gut health:

- Fermented and pickled foods

- Live yoghurt, kefir,

- Aged cheeses

- Miso soup, tempeh,

- Kimchi,

- Natto,

- Sauerkraut

- A good quality probiotic supplement (see below)

Certain foods can help promote the growth of healthy bacteria and impede the formation of unhealthy bacteria. Some, such as mushroom, have anti-biotic properties which directly kill unhealthy bacteria. These foods also protect bacteria from the enzymes in the saliva and stomach, enabling the formation of healthy colonies in the small bowel and colon. Pre-biotic-rich foods consist of two main categories

Soluble fermentable fibres include Inulin; Starches such as sucoligosaccharides and fructooligosaccharide found in and other Polysaccharide beta-glucans. These are mainly found in:

- Chicory, leeks and asparagus, onions garlic

- Onions, asparagus, wheat, tomatoes beans and grains

- Fruits, vegetables and mushrooms

- Guar gum and psyllium.

Polyphenol prebiotics include plant lignans ; ellagic acid into ellagitannin

- Nuts,

- Bananas

- Beans

- Citrus fruit such as pears, apples, cranberries, pomegranate

- Beans such as chickpeas, peas, kidney beans

- Vegetables and roots, broccoli, asparagus, chicory root and artichoke,

- Grains and seeds such as barley, oats and linseeds

- Resveratrol in grapes and red wine

- Spices such as garlic, turmeric and chile

- Tea and unsweetened chocolate

Pre-biotic phytochemical rich supplements can be a convenient way to boost the diet, spread the intake of these foods throughout the day. It is particularly important to start eating these food from first thing in the morning. There is some evidence for boosting phytochemical intake with a supplement. For example, Phyto-V was chosen for the National Covid-19 nutritional intervention study which reported it significantly helped to improve acute and long covid symptoms, especially fatigue, gut symptoms and overall quality of life. In the latest prostate study YourPhyto worked with probiotics to reduce prostate cancer progression.

A note about the FODMAP diet – Removal of prebiotic and fermented foods can help bloating and IBS like symptoms in the short term short term but this is not a long term benefit and in the long term can be counter productive.

Food intolerance test – if you have not identified a food, most often milk or gluten, which causes bloating, usually by trial and error – it may be worth investing in a food allergy test.

..

Role for Probiotic Supplements

As a rule, we should all be concentrating on the lifestyle and nutritional advise, highlighted above but a good quality supplement is a convenient way to increase the intake of healthy prebiotic bacteria and prebiotics especially in the UK population which is traditionally low in foods which contain them.

Potential benefits of probiotic supplements inside the gut

Travellers diarrhoea: Certain strains of probiotics have been shown to be effective at treating diarrhoea and gastroenteritis commonly caught whilst travelling, usually from drinking water. A study published in the Journal of Pediatrics concluded that Lactobacillus species are a safe and effective form of treatment for children with infectious diarrhoea. Other studies have shown that prophylactic use of probiotics containing Lactobacillus significantly reduce the risk of nosocomial diarrhoea in infants, especially nosocomial rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Antibiotic-induced diarrhoea: Antibiotics play a vital role in treating bacterial infections but have the unfortunate side effect of also reducing healthy bacteria in our gut, altering the natural balance of the microflora, causing bloating and diarrhoea. A report published in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition indicated that probiotics were helpful in the prevention or treatment of antibiotic-induced diarrhoea, especially in children.

Bacterial food poisoning: Most acute diarrhoea episodes are caused by viruses but some, especially those caught by ingesting infected food, can be bacterial. A study published in ‘Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences’, found that probiotic bacteria can help protect against bacterial infections such as Listeria and the superbug Clostridium difficile infection. Some hospitals are giving people probiotics before going into hospital in order to reduce their risk of infection.

Chemotherapy-induced diarrhoea: Several chemotherapy agents commonly cause diarrhoea due to damage these agents inflict on the cells lining the gut. If severe, as well as being very distressing and uncomfortable for the patient, this can lead to dehydration, concentration of the chemotherapy in the bloodstream and, eventually, renal damage. A number of placebo-controlled randomised trial have shown that lactobacillus probiotics can reduce chemotherapy induced diarrhoea from 5 fluoruracil and irinotecan..read studies

Other chemotherapy side effects: Even without diarrhoea, a course of intense chemotherapy can cause significant damage to the gut microbiome, leading to increased symptoms of fatigue, joint aches, indigestion and nausea. Many cancer centres such as Memorial Sloane kettering strong recommend lifestyle and nutritional strategies to improve gut health, the use of lactobacillus probiotic supplement and even in sum studies autofaecal transplant! A recent summary (systemic review) of 20 studies showed that lactobacillus probiotics are safe during chemotherapy and 85% of them revealed that probiotics reduced the incidence of treatment-related side effects in oncology patients. While 15% reported no impact in their findings, no study reported any harm..read more

Immunotherapies: Having poor gut health will increase the chances of toxicity including diarrhoea and pulmonary inflammation. Trial are emerging showing that people with poor gut health have up to 40% lower chance these treatments working including for tumours such as glioblastoma, melanoma, lung, breast, bowel cancers and sarcomas… read more

Radiotherapy bowel problems: Several well-conducted trials have demonstrated that probiotics can help prevent radiation bowel damage and aid recovery after radiotherapy – read more

Wheat and Lactose intolerance: As you get older, it’s common to develop an intolerance to gluten found in wheat and other grains. This causes IBS like symptoms with bloating and colicky pains. Reducing the intake of bread, pasta and cereals should always be the first measure taken, but a number of studies have demonstrated how probiotic intake can also be helpful. Intolerance to milk also is becoming more common, usually the result of a lactase deficiency. Lactase is an enzyme normally produced in your small intestine. It is needed to break down lactose and to enable you to digest milk. The probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus helps with the digestion and absorption of lactose by producing lactase.

Potential benefits of probiotic supplements outside the gut

Vitamin D absorption: As a fat soluble vitamin, the absorption of vitamin D is strongly linked to a healthy gut. A number of studies have linked the intake of a good quality probiotic supplement together with vitamin D supplements with higher blood levels of vitamin D3 [Jones]. Adequate vitamin D is important for a wide number of chronic disease including bone health and immunity – low levels have recently been linked to higher problems related to covid-19 [Jones].

Cancer: Preliminary experiments in animals have found that stimulating growth of healthy bacteria in the colon leads to the inhibition of colon carcinogenesis. It has been suggested that this is due to their pH-lowering effect in the colon, which subsequently inhibits the growth of unhealthy (pro-inflammatory) bacteria such as E.coli and clostridia. A decrease in the growth of pathogenic microorganisms also modulates bacterial enzymes that convert pro-carcinogens to carcinogens. In humans, taking regular probiotics has been linked to a lower rate of new polyp formation and bowel cancer relapse. Probiotic bacteria help produce butyrate, an acid which feeds healthy gut wall cells but also exerts a direct effect on cancer cells by turning off genes involved in cell growth and turning on genes that trigger cell suicide (apoptosis). Early research has shown that butyrate can block the growth of colon cancer cells in vitro, and experiments in mice suggest that dietary intake of probiotics and/or prebiotics with soluble fibre may increase butyrate production and slow tumour development. Besides fibre, healthy gut bacteria can convert polyphenols, into range of cancer-preventive chemicals including phenols and urolithins, produced from ellagic acid found in pomegranates and isothiocyanate, found in broccoli.

Therefore a high fibre and polyphenol-rich diet can increase the abundance of cancer-preventive, butyrate-producing bacteria in the gut. On the other hand, a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets, changes fermentation in the intestine, leading to increased levels of harmful nitrosamines, and decreased levels of protective molecules like butyrate and phenols. Other research suggests that a high-fat diet can change the microbiome in a way that increases production of the bile acid DCA, which promotes colon and oesophageal cancers.

Chronic inflammation: An overactive immune system leads to excess inflammatory cytokines which can cause numerous chronic diseases including arthritis, dementia, cancer and heart disease. The best anti-inflammatory diet is the macrobiotic diet, which features lots of fermented foods such as miso soup, kefir and kimchi. UK diets are traditionally low in these bacteria-rich foods.

Arthritis: People with arthritis often have suboptimal gut health. One study gave a probiotic capsule to people with arthritis for 8 weeks and found that several markers of joint oxidative stress decreased significantly. In another study, patients who took two probiotic capsules a day for 12 months experienced a reduction in the number of tender and swollen joints, while also displaying reduced inflammatory markers such as IL-1β.

Bone health: Probiotic bacteria

Blood Pressure: There is emerging evidence that probiotics may have a role in cardiovascular health. A meta-analysis of nine studies, published in the journal Hypertension, tracked over 543 adults with both normal and high blood pressure and found that, on average, taking probiotics lowered systolic blood pressure by 3.56 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 2.38 mmHg. The greatest effects were seen in subjects with BP above 130/85 and those who took probiotics with multiple strains were more likely to experience a lowering of BP than those taking single-strain sources.

Fatty liver and metabolic syndrome: Too much fat accumulating in the liver affects its function, eventually leading to damage. Several factors can cause a fatty liver, defined as fat stores >10% of its volume, including obesity, diabetes, alcohol abuse, poor diet and genetic susceptibility. Although there are no significant studies evaluating humans, researchers recently discovered that Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium probiotic strains prevented the accumulation of fat in the liver of obese rats. Markers of inflammation (tumour necrosis factor and interleukin 6) and triglyceride counts also improved. In another animal study, mice were fed a high-fat diet for eight weeks and given either probiotics or a placebo. Mice who received the bacteria ate significantly less than the placebo group, had lower insulin levels and body fat, and reduced their fatty liver deposits. Trials in humans are planned.

Obesity: Obese patients usually have a poor microflora, which in turn promotes inflammation and storage of fats, leading to further weight gain. A number of studies have demonstrated that some probiotics taken before a meal reduce overall calorie intake [Hume].

Eczema: There is a clear link between poor gut health an eczema. The role for probiotics is not established. Some trial do show a benefit and others do not. A recent chocrane overview showeHowever, we did find that these probiotics may slightly reduce the severity of eczema scored by patients and their healthcare professionals in combination (low-quality evidence), although it is uncertain if such a change is meaningful for patients.

Cholesterol levels: Research presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions in 2012 reported that a formulation of Lactobacillus may be able to reduce blood levels of LDL (bad cholesterol).

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Scientists at the University of Cork reported in the journal Gut Microbes that Bifidobacterium may have benefits for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.

Iron absorption: A trial from Gothenburg, Sweden published in 2015 showed that women taking a lactobacillus probiotic supplement were able to increase natural iron absorption from food [Hoppe].

Which probiotic supplement?

There are thousands of probiotics available on the market, many claiming attributes over others. The reality is that there are no scientifically robust studies comparing one brand over another so it’s hard to know which is the best. Most of the evidence highlighted above involves supplements containing lactobacillus so it would be good to ensure these are in the blend. The over the count blend called Yourgutplus+ was used in three national clinical trials and was found to be safe, well tolerated and effective. It also contains a good quantity of prebiotic inulin and vitamin D and has a delayed released vegan capsule ..read more

..

Source information and references

- Thomas R, et al (2021) The Influence of a blend of Probiotic Lactobacillus and Prebiotic Inulin on the Duration and Severity of Symptoms among Individuals with Covid-19. Infect Dis Diag Treat 5: 182. DOI: 10.29011/2577-1515.100182

- Thomas, R. et al . A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial Evaluating Concentrated Phytochemical-Rich Nutritional Capsule in Addition to a Probiotic Capsule on Clinical Outcomes among Individuals with COVID-19—The UK Phyto-V Study. COVID 2022, 2, 433-449. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2040031

- Bultman S: The microbiome and its potential as a cancer preventive . Semin Oncol 43:97-106, 2016

- Schwabe RF: The microbiome and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 13:800-12, 2013

- Viaud S. Gut microbiome and anticancer immunity: really hot Sh*t! Cell Death Differ 22:199-214, 2015

- Shahanavaj K: Cancer and the microbiome: . Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 15:317-30, 2015.

- Russo E: The interplay between the microbiome and immune response. Therapy Adv Gastrol 9:594, 2016.

- Pevsner-Fischer M: Role of the microbiome in non-GI cancers. World J Clin Oncol 7:200-13, 2016

- Poutahidis T: Gut microbiota and the paradox of cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 5:157, 2014

- Zitvogel L et al: Microbiome and Anticancer Immunosurveillance. Cell 165:276-87, 2016

- Gopalakrishnan V: Diversity and the gut microbiome in responses to PD-1 therapy. J Clin Oncol 35, 2017

- Vetizou M : Anticancer immunotherapy relies on the gut microbiota. Science 350:1079-84, 2015

- Sivan A: Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1. Science 350:1084-9, 2015

- Pitt JM: Fine-Tuning Cancer Immunotherapy: Optimizing the Gut Microbiome. Cancer Res 76:4602-7, 2016

- Prevention of irinotecan-induced diarrhoea by probiotics: RCT study. J Clin Oncology. Mego M et al 32:5s, 2014 (s 9611).

- Hoppe M et al Probiotics increases iron absoption from fruit: a doubleblind cross over trial. British Journal of Nutrition 114,1195-1202

- Hume M et al Prebiotic supplementation improves appetite control in children with obesity: a RCT. Am J Clin Nutrition 2017. 22, 2017,

- Abrams SA et al Effect of prebiotic supplementation and calcium intake on body mass index. J Pediatr. 2007;151(3):293-8.

- Health claims substantiation for probiotic and prebiotic products. Sanders M et al. 2011, Gut Microbes, 2 (3), 127-133.

- Safety assessment of probiotics for human use. Sanders M, Akkermans L et al 2010 Gut Microbes, 1 (3) pp 164-185.

- Klein M et al. Probiotics: From Bench to Market. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (2010) DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05839.x

- Guide to designing, conducting, studies involving probiotics. (2010) Gut Microbes Shane A, Michael D. Cabana M et al, Vol 1 (4) pp 243-253.

- Food Formats for Effective Delivery of Probiotics. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology. 2009 Saunders M and Marco M. Vol. 1: 65-85.

- How Do We Know When Something Called “Probiotic” Is Really a Probiotic? A Guideline for Consumers and Health Care Professionals (2009).

- Saunders M: Probiotics: Their potential benefit to human health. J of the council for ag science and tech 2011 Oct 2011.

- Probiotics in the management of chemo-induced diarrhoea. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2009. 33 (5) 569-70.

- Chiang S et al. Antiosteoporotic effects of Lactobacillus on bone mineral density. J Agric Food Chem. 2011, 27; 59(14):7734-42

- Yacon F et al Bifidobacterium longum modulate bone health in rats. J Med Food. 2012; 15(7):664-70.

- Ohlsson C et al Probiotics protect mice from ovariectomy-induced cortical bone loss. PLoS One. 2014; 17; 9(3):e92368.

- Reid G et al. New scientific paradigms for probiotics and prebiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003; 37(2):105-18.

- Delia et al Probiotics and radiotherapy bowel damage. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007; 13(6), 912

- Jones M et al. Oral supplementation with lactobacillus probiotic increases mean circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D: a RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2944–2951. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4262. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Other Reference sources for gut health:

Other Reference sources for gut health:

“How to Live” published by short books written by Professor Robert Thomas

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3065426/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3983973/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4425030/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6378305/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26358192

https://www.dovepress.com/the-influence-of-prebiotic-or-probiotic-supplementation-on-antibody-ti-peer-reviewed-article-DDDT