Sensitivity and tenderness of the breast tissue itself are common before puberty, throughout pregnancy and at certain times during the menstrual cycle. At other times, breast tenderness may reflect an underlying problem such as:

Sensitivity and tenderness of the breast tissue itself are common before puberty, throughout pregnancy and at certain times during the menstrual cycle. At other times, breast tenderness may reflect an underlying problem such as:

- Trauma and bruising

- Infection

- Benign fibrocystic disease

- Breast cancer

- Reaction to surgery or radiotherapy

Unexplained tenderness should be reported to your doctor and investigated, especially if associated with symptoms such as:

- Lump(s) in the breast or under the arm

- Swelling of the breast

- Tethering of the skin

- Inversion of the nipple,

- Nipple discharge

- Discolouration of the skin

After breast surgery (including mastectomy) a variety of different pains can occur, primarily due to disruption of the normal architecture of the breast or chest wall and the subsequent disturbing of fluid flow around it. Not only will this cause a throbbing, aching discomfort, but it also makes the breast heavier and hotter, straining the underlying muscles. Surgery also cuts the minor nerves in the breast and under the arm, often causing numbness. When these attempt to repair themselves, the numbness usually gives way to a burning, over-sensitive pain (hyperaesthesia), which can last for several years. Additionally, the disrupted nerves can send sharp, jabbing pains into the breast. These neuralgic pains may only last a few seconds, but they are enough to make your toes curl! If these neuralgic pains become severe, medication such as gabapentin can be prescribed.

After surgery for breast cancer, radiotherapy is usually recommended if a lump has been removed and, on occasion, also after a complete mastectomy. Although technological advances have reduced side effects, the skin can still become red and itchy for 3-6 weeks. In the long-term, radiotherapy can contribute to the underlying thickening and fibrosis of the tissues between the skin and the breast. In time, without the interventions highlighted below, this could lead to shrinkage of the breast or contraction of the tissues after mastectomy, leading to even further discomfort. Some of these pains can be cyclical, exacerbated at different times of the month as hormone levels fluctuate.

What can you do to help?

For puberty, premenstrual and pregnancy pains, there are very few lifestyle strategies which are effective other than avoiding trauma and wearing a comfortable, well-fitted bra. For chronic pains caused by benign fibrotic disease or previous breast treatment, there is a great deal which can be done to reduce pain and prevent further deterioration of symptoms. These can be broadly split into the following strategies:

- Local exercises and stretches

- Local massage

- General lifestyle measures

Local strategies to help reduce breast discomfort

Whatever the cause of breast pains, it’s important to break down scars and fibrosis between the breast tissue and the surrounding skin, muscles, joints and nerves. If performed regularly, this will improve blood supply, aid lymphatic drainage, and enhance the mobility, flexibility and compliance of the breast tissue, skin, and the underlying muscle and ribs. It is important to realise that this is a slow process. Most people give up stretching and exercise within 6 weeks if they don’t immediately feel a benefit, but clinical trials suggest improvements are usually only noticed after several months and confirm that exercises need to be performed daily and indefinitely. In fact, women may not notice any perceivable improvements at all but are still doing themselves a favour by preventing further deterioration.

Local exercises and stretching designed to help relieve breast pains

After surgery, moving your arm or upper chest is often associated with pain caused by tissues not gliding smoothly across each other. Gradually, the discomfort will ease, but exercises should be continued, even when the tenderness appears to have resolved. The following exercises are recommended.

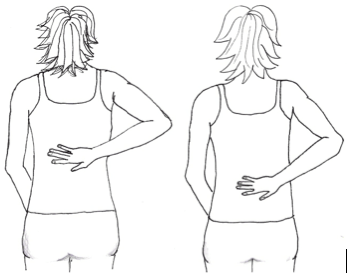

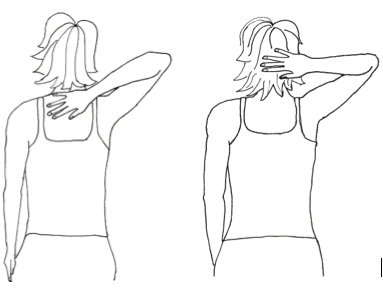

Finger walking (back): Now do the same thing to the lower back. Lower your hands to the base of the spine and walk your fingers up and down the spine. Once comfortable, add a bit of a twist by pushing the tips of the fingers across the midline of the spine and rotating your body in the same direction. This is good for the back and also adds an extra stretch across the chest wall. Aim to repeat ten times.

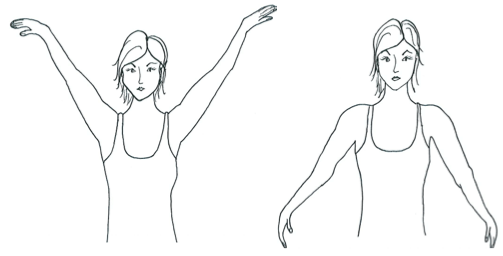

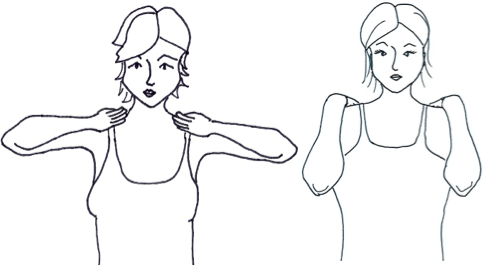

Big bird: Place arms by the side of your body, standing upright. Raise and lower your straight arms as high as possible. This should look like a big bird flapping its wings slowly. Aim to repeat ten times.

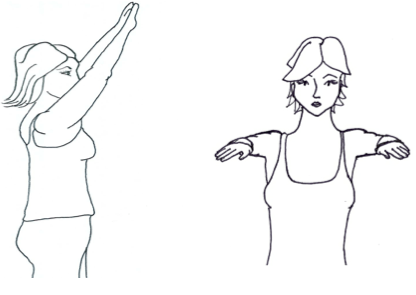

Twist and fan: With your arms out in front of you, turn your palms up and then down. With straight arms, raise your hands above your head, as straight as possible. You should feel a stretch on the side of your chest wall and the muscles aching in your upper back. Aim to repeat ten times.

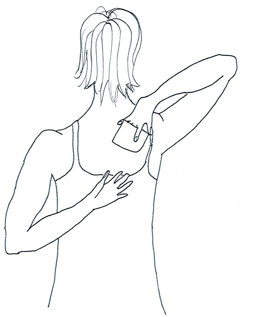

The hand over: Putting your right hand behind your back, pass a small, light object across your back, over your left shoulder to the other hand. Repeat and swap hands. The ability to do this may depend on your previous flexibility. Alternatively, you could use an exercise band.

Massage

Gentle manipulation of the breast and surrounding skin can stimulate blood supply and break down adhesions. Although this should be avoided during radiotherapy, when the skin may be a little red and sore, there is zero evidence to suggest that massage is harmful or should be avoided after a diagnosis of cancer. Use a natural oil, such as extra virgin olive oil, rather than commercial oils containing perfumes and additives. Apply the oil with the fingers gently and roll the skin over the ribs with firm pressure, all the while avoiding any further aggravation of pain or bruising. At first, there will not be any noticeable improvement, but with daily persistence, pain and mobility will improve.

General lifestyle measures

It would be useful to reduce the amount of chronic inflammation in your body by reducing exposure to harmful chemicals, developing healthier habits and increasing intake of natural foods which have anti-inflammatory properties.

Smoking: Smoking significantly increases the fibrosis and thickening of underlying tissues. It causes inflammation of the breast glands and an increased risk of fibrocystic disease, leading to cysts and blocked ducts.

General exercise: Markers of chronic inflammation are higher among individuals who are overweight, sedentary and have poor diets. One reason for this stems from an ailing immune system overcompensating in order to try and maintain function. To compensate for this, higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers are produced, which increase concentrations of immune cells such as natural killer cells and T lymphocytes. Exercise is known to enhance natural killer cell activity and increase T-cell production, reducing the need for the immune system to compensate by increasing the circulation of inflammatory biomarkers.

Prostaglandins, which are biologically active lipids generated from arachidonic acid via the enzyme cyclo-oxidase (COX), also influence chronic inflammation. The COX-1 enzymes are present in normal tissues and up-regulate in response to trauma, infection or chemical injury, increasing prostaglandins, which in turn trigger an appropriate inflammatory cascade. Chronically increased overproduction of prostaglandins, generated via COX-2, has been implicated in tissue fibrosis and even cancer progression. Studies have shown that moderate, regular, non-traumatic exercise reduces serum prostaglandin levels.

Diet

A dietary change should aim to reduce the intake of foods which promote chronic inflammation while increasing consumption of foods which have anti-inflammatory properties.

Carcinogens: It would be a good idea to reduce the number of man-made chemicals and additives in the food by omitting most processed foods and those with artificial colourings and flavourings. There are some reports that these create inflammatory reactions in the body.

Sugar: There are several laboratory studies which show that processed sugar and carbohydrates, alongside foods with a high glycaemic index, promote chronic inflammation. This was highlighted by an experiment where half a group of mice were fed sucrose with their usual meal at comparable levels to Western diets, while the other half were given a normal diet. The western diet led to increased expression of inflammatory markers, including 12-lipoxygenase (12-LOX) and its arachidonate metabolites

Phytochemicals: Some phytochemical-rich foods have direct anti-inflammatory properties, so it makes sense to try and incorporate these into a diet. The green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), alongside quercetin found in onions, have both been shown to suppress activation of the NF-kappaB family of transcription factors which trigger immune and inflammatory pathways. Cruciferous vegetables are also potent inducers of transcription factors, as demonstrated in a study which highlighted how rats fed a broccoli-rich diet experienced a reduction in the activation and production of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin [Thomas]. Another recent animal trial, led by the School of Biological Sciences and Norwich Medical School, found that cruciferous vegetable extract also blocked histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor as well as matrix metalo-proteinase expression, which resulted in a protective effect on tissues and joints [Thomas]. Many dark green vegetables, as well as herbs such as ginger and turmeric, contain natural salicylates which block both COX-1 and 2, reducing the inappropriate production of prostaglandins. Making a fresh ginger and turmeric tea daily is a good idea – an example is demonstrated below.

Plant and fish oils: Omega 3, found in oily fish and grass-fed meat, is thought to have anti-inflammatory properties, but taking extra amounts in clinical trials has not shown any significant benefits. Nevertheless, many people in the UK are deficient in omega 3 and increasing intake of oily fish to at least three times a week is recommended. Omega 6, such as linoleic acid (LA), is thought to promote inflammation as it is a precursor for arachidonic acid. This is found in healthy nuts and vegetable oils, and there is some controversy over how much should be consumed in a healthy diet.

Summary

- Regularly perform local breast exercises

- Regularly perform shoulder and neck exercises

- Consider physiotherapy if self measures fail

- Wear a good fitting bra when exercising

- Gently massage your breast with olive oil or another natural alternative

- Gently massage the skin around your breast and armpit

- If you smoke, stop, as this increases thickening in the breast

- Consider an anti-inflammatory diet rich in healthy fish oils

- Increase ginger in the diet such as in herbal teas

- If these measures fail, it may be worth trying a supplement of evening primrose or a phytochemical-rich blend

References

- Yang J et al. Sucrose-Enriched Diet Promotes 12-Lipoxygenase (inflammatory) pathway. 2015 Cancer Res; 76(1); 24–29.

- Cooper R et al. Medicinal benefits of green tea: Review of non-cancer health benefits. J Altern Com Med. 2005;11:521–528.

- Traka M et al 2009. Glucosinolates, isothiocyanates and human health. Phytochemistry Reviews 2009 (8), 269-282.

- Thomas R et al. Phytochemicals in cancer prevention and management? BJMP 2015 (8) 2, pp 34-38.

- Thomas et al. Exercise-induced biochemical changes and their potential influence on cancer: a scientific review. 2016 British Journal of Sports Medicine